Introduction to Spiral Motion Systems

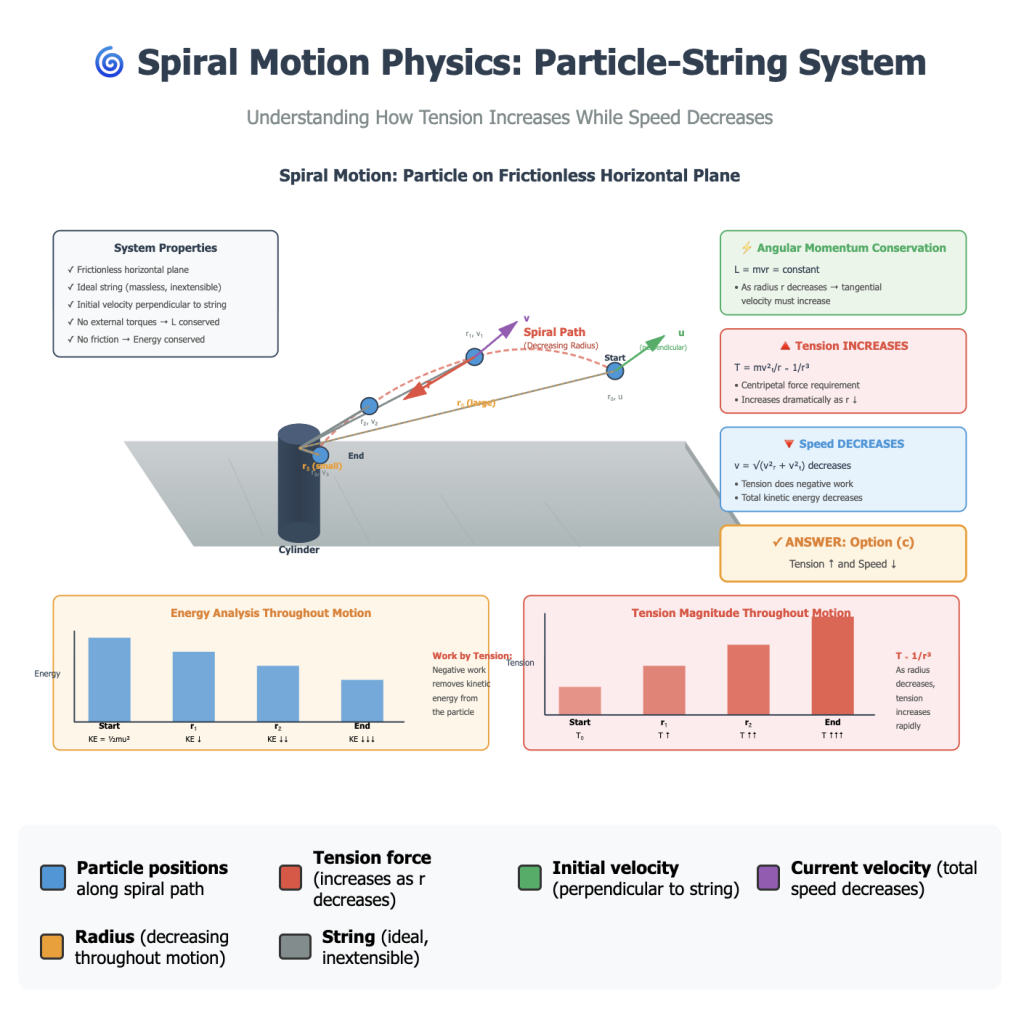

The physics of particles constrained by strings moving in spiral paths represents one of the most fascinating applications of classical mechanics. This scenario combines multiple fundamental concepts including circular motion, conservation laws, and force analysis. The problem presented involves a particle of mass m attached to an ideal string, where the other end is connected to a vertical cylinder on a frictionless horizontal plane. When the particle is projected perpendicular to the string, it traces a spiral path of decreasing radius until it strikes the cylinder.

This problem is not merely an academic exercise; it reveals deep insights into how physical systems behave when multiple constraints operate simultaneously. The question asks us to determine how the tension in the string and the speed of the particle change as it moves along the spiral path. The answer, which might seem counterintuitive at first, is that tension increases while speed decreases (option c).

Understanding why this happens requires a comprehensive exploration of the underlying physics, including the conservation of angular momentum, the role of centripetal force, and the work-energy theorem. This article will provide a thorough analysis that makes this complex topic accessible to students and physics enthusiasts alike.

Understanding the Physical Setup

The Components of the System

The system consists of several key elements that define its behavior:

- The Particle: A point mass m that serves as the primary object of study. The particle has initial kinetic energy and momentum when projected into motion.

- The String: Described as “ideal,” meaning it is massless, inextensible (doesn’t stretch), and perfectly flexible. The string can only exert tension forces along its length, never perpendicular to it.

- The Cylinder: A vertical cylinder fixed to a frictionless horizontal plane. The cylinder serves as the anchor point for the string and the eventual target for the particle.

- The Horizontal Plane: Described as frictionless, which is crucial because it means no energy is dissipated through friction, and the vertical component of motion can be ignored.

Initial Conditions

The particle is projected with an initial speed u in a direction perpendicular to the string. This perpendicular projection is essential because it means:

- The initial velocity has no component along the string direction

- All initial motion contributes to tangential velocity

- The particle begins with maximum angular momentum for the given speed

The Spiral Path

As the particle moves, it traces a spiral path with a decreasing radius. This is not circular motion because the radius continuously changes. The spiral nature arises from the specific initial conditions and the constraints imposed by the string.

Fundamental Physics Principles

Newton’s Second Law

The foundation of our analysis rests on Newton’s second law: F = ma. For the particle moving in a curved path, we must consider forces in multiple directions:

- Radial Direction: The tension in the string provides the centripetal force needed for circular motion. As the radius changes, so does the required centripetal force.

- Tangential Direction: Since the plane is frictionless and the string can only pull radially inward, there is no tangential force. This has profound implications for the motion.

Conservation Principles

Two conservation laws are particularly relevant:

- Conservation of Angular Momentum: In the absence of external torques about the cylinder’s axis, angular momentum remains constant. This is the key to understanding the entire system’s behavior.

- Conservation of Energy: While mechanical energy is conserved (no friction), the distribution between kinetic energy and the work done by tension changes as the particle spirals inward.

Circular Motion Fundamentals

Even though the path is a spiral, at each instant, the particle undergoes circular motion with a particular radius. The centripetal acceleration is given by v²/r, where v is the instantaneous speed and r is the instantaneous radius.

Conservation Laws in Action

Why Angular Momentum Conserves

Angular momentum L is defined as L = mvr sin(θ), where θ is the angle between the velocity vector and the position vector from the axis. For our setup:

- The particle moves on a horizontal plane

- The cylinder’s axis is vertical

- The string tension is always radial (pointing toward the cylinder)

Since tension acts radially, it produces zero torque about the cylinder’s axis. With no external torque, angular momentum about this axis is conserved.

Mathematical Expression of Angular Momentum

Initially, when the particle is at distance r₀ from the cylinder and moving with speed u perpendicular to the string:

L₀ = m × u × r₀

At any later time, when the radius is r and the speed is v:

L = m × v × r × sin(θ)

However, since the velocity remains perpendicular to the radius (the string only pulls radially, providing no tangential force), sin(θ) = 1, and:

L = mvr

The Conservation Equation

Setting the initial and final angular momenta equal:

mvr = mu₀r₀

This simple equation is the key to understanding the entire problem. It tells us that as r decreases, v must adjust to keep the product constant.

Angular Momentum Analysis

Implications of Constant Angular Momentum

The conservation equation mvr = constant reveals a fundamental relationship: the product of speed and radius remains constant. This means:

As radius decreases → speed must increase?

Wait—this seems to contradict the correct answer that speed decreases! This apparent paradox requires careful examination.

Resolving the Apparent Paradox

The resolution lies in understanding that not all of the particle’s velocity contributes to angular momentum—only the tangential component does. As the particle spirals inward:

- The tangential velocity component follows: v_tangential × r = constant

- But the particle also develops a radial velocity component (moving toward the cylinder)

- The total speed v = √(v_tangential² + v_radial²)

Tangential vs. Total Velocity

Let’s denote:

- v_t = tangential velocity component

- v_r = radial velocity component

- v = total speed = √(v_t² + v_r²)

From conservation of angular momentum: v_t × r = u × r₀ = constant

Therefore: v_t = (u × r₀)/r

As r decreases, v_t increases. However, the total speed v actually decreases because of energy considerations.

Tension Force Dynamics

The Role of Tension

The string tension T serves multiple purposes:

- Provides centripetal force for the tangential motion component

- Decelerates the radial motion component

- Does negative work on the particle as it moves inward

Centripetal Force Requirement

For the tangential motion component, the required centripetal force is:

F_centripetal = m × v_t²/r

Since v_t = (u × r₀)/r, we have:

F_centripetal = m × (u × r₀)²/r³

This expression shows that as r decreases, the required centripetal force increases dramatically (inversely proportional to r³).

Tension Must Exceed Centripetal Requirement

The actual tension must be greater than just the centripetal requirement because it also must:

- Slow down the radial velocity component

- Account for the particle’s inward spiral motion

The tension can be expressed as:

T = m × v_t²/r + m × a_r

where a_r is the radial acceleration (which is negative, representing deceleration of inward motion).

Why Tension Increases

As the radius decreases:

- The centripetal force requirement increases as 1/r³

- The tangential velocity increases as 1/r

- The combined effect causes tension to increase significantly

Speed Variation During Spiral Motion

The Energy Perspective

To understand why the total speed decreases, we must analyze energy. The system’s mechanical energy is conserved, but energy is redistributed between kinetic energy and the work done by tension.

Initial kinetic energy: KE₀ = ½mu²

At radius r with speed v: KE = ½mv²

Work Done by Tension

As the particle moves from radius r₀ to radius r, the string tension does work. Since the particle moves inward (opposite to the tension’s direction would naturally pull), and tension is always pulling inward, the work done is:

W = ∫ T × dr (from r₀ to r)

This work is negative because the particle moves inward while tension pulls inward, but the particle is slowing down overall.

Energy Conservation Equation

The work-energy theorem states:

½mv² = ½mu² – |W_tension|

Since work is negative (removes energy from the system from the particle’s perspective), the kinetic energy decreases, meaning the speed decreases.

Alternative Energy Analysis

Another way to see this: as the particle spirals inward, the tangential kinetic energy increases (since v_t increases), but the total kinetic energy must account for the work done against tension. The radial component’s kinetic energy changes, and the net effect is that total speed decreases.

Mathematical Framework

Complete Set of Equations

For a comprehensive mathematical treatment, we need:

1. Conservation of Angular Momentum:

mvr sin(α) = mu₀r₀where α is the angle between velocity and radius.

2. Newton’s Second Law (Radial):

-T = m(dv_r/dt - v_t²/r)3. Newton’s Second Law (Tangential):

0 = m(dv_t/dt + v_r×v_t/r)4. Energy Conservation:

½m(v_r² + v_t²) + U_effective = ½mu²Solving for Tension

From the angular momentum equation and the radial force equation, we can derive:

T = m(u₀r₀)²/r³ + m × a_r

As r decreases:

- First term increases as r⁻³

- Second term (involving radial acceleration) also contributes to increase

Solving for Speed

From energy conservation and angular momentum:

v² = v_r² + v_t²

where v_t = u₀r₀/r

The detailed solution requires solving a differential equation, but qualitatively, we can show that v decreases as r decreases.

Step-by-Step Problem Analysis

Step 1: Identify the Initial State

- Particle at distance r₀ from cylinder

- Moving with speed u perpendicular to string

- Tension T₀ = mu²/r₀ (initial centripetal force)

- Angular momentum L₀ = mu₀r₀

Step 2: Identify Constraints

- String is inextensible and ideal

- Plane is frictionless (no energy loss)

- Motion occurs in horizontal plane

- String remains taut (always under tension)

Step 3: Apply Conservation Laws

- Angular Momentum: Since no external torque acts about the vertical axis through the cylinder, angular momentum is conserved.

- Energy: No friction means mechanical energy is conserved, though it’s redistributed between different forms.

Step 4: Analyze Forces

At any radius r:

- Tension T acts radially inward

- No tangential forces (frictionless plane)

- No vertical forces (motion in horizontal plane)

Step 5: Determine Tension Behavior

From centripetal force requirement: T ≥ mv_t²/r = m(u₀r₀)²/r³

As r decreases, r³ decreases faster, so T must increase.

Step 6: Determine Speed Behavior

From energy conservation:

- Initial KE = ½mu²

- Final KE = ½mv² = ½m(v_r² + v_t²)

- Work done by tension removes energy

- Therefore v < u as r < r₀

Step 7: Conclusion

- Tension increases (due to 1/r³ dependence)

- Speed decreases (due to negative work by tension)

Answer: Option (c) – Tension will increase and speed will decrease

Why Tension Increases

The Centripetal Force Argument

The most straightforward reason tension increases is the centripetal force requirement. As the particle spirals inward:

- Radius decreases: The turning radius becomes smaller

- Tangential velocity increases: From angular momentum conservation, v_t ∝ 1/r

- Centripetal acceleration increases: Since a_c = v_t²/r, and v_t ∝ 1/r, we have a_c ∝ 1/r³

- Tension must provide this force: T ∝ ma_c ∝ 1/r³

The Physical Intuition

Imagine a figure skater performing a spin. As they pull their arms inward:

- They spin faster (conservation of angular momentum)

- They must exert more force to keep their arms moving in circles

- The tension in their muscles increases

The same principle applies to our particle-string system.

Quantitative Analysis

If initially at radius r₀ with tension T₀ = mu²/r₀, then at radius r = r₀/2:

T ≈ m(ur₀/r)²/r = m(2u)²/(r₀/2) = 8mu²/r₀ = 8T₀

The tension increases by a factor of 8 when the radius halves!

Why Speed Decreases

The Energy Argument

The most rigorous explanation comes from energy analysis:

- Initial Energy: E₀ = ½mu²

- Energy at radius r: E = ½mv² + Work done by tension

Since the system is conservative (no friction), but tension does negative work as the particle moves against the tension’s pull:

½mv² < ½mu²

Therefore: v < u

The Work-Energy Analysis

As the particle moves from radius r₀ to r (where r < r₀):

Work by tension = ∫(r₀ to r) T·dr

This integral is negative because:

- The particle moves inward (dr < 0)

- Tension pulls inward (T points toward decreasing r)

- The dot product T·dr < 0

This negative work reduces the particle’s kinetic energy, hence reducing its speed.

The Component Velocity Analysis

While the tangential component v_t increases, the total speed is:

v = √(v_t² + v_r²)

The radial component v_r represents the rate at which the particle approaches the cylinder. As the spiral tightens:

- v_t increases (to conserve angular momentum)

- But v_r must decrease (the particle is decelerating inward)

- The net effect is that v = √(v_t² + v_r²) decreases

Physical Intuition

Think of the string as constantly “fighting” the particle’s motion. As the particle tries to move inward, the string tension:

- Pulls it into a tighter circle (increasing tangential speed)

- But simultaneously removes energy from the system

- The overall effect is like a brake that slows the total speed

Common Misconceptions

Misconception 1: “Angular momentum conservation means speed increases”

- The Error: Confusing tangential velocity with total speed.

- The Truth: Angular momentum conservation (mvr = constant) means tangential velocity increases as radius decreases, but total speed (which includes radial velocity) actually decreases due to energy considerations.

Misconception 2: “No friction means no forces slow the particle”

- The Error: Assuming frictionless means no deceleration.

- The Truth: The string tension itself does negative work on the particle, removing kinetic energy and reducing speed. Friction is not the only force that can slow objects down.

Misconception 3: “Tension remains constant like in uniform circular motion”

- The Error: Applying uniform circular motion concepts to non-uniform motion.

- The Truth: This is spiral motion with changing radius, not uniform circular motion. The centripetal force requirement changes dramatically as radius changes.

Misconception 4: “Both quantities should change in the same direction”

- The Error: Assuming correlated behavior without analyzing the underlying physics.

- The Truth: Different physical mechanisms govern tension (centripetal force requirement) and speed (energy conservation), leading to opposite trends.

Misconception 5: “The particle falls into the cylinder”

- The Error: Misunderstanding the geometry and forces.

- The Truth: The particle spirals inward on a horizontal plane, maintaining its height while the radius decreases. It doesn’t “fall” but rather spirals due to the string constraint.

Real-World Applications

Planetary Orbits and Satellites

When satellites lose altitude due to atmospheric drag, they experience:

- Decreasing orbital radius

- Increasing orbital speed (tangential)

- But overall energy decreases

This is analogous to our spiral motion problem.

Centrifugal Separators

In industrial centrifugal separators, particles spiral outward or inward depending on density. Understanding how velocity and forces change with radius is crucial for:

- Optimizing separation efficiency

- Designing appropriate container strengths

- Calculating processing times

Atomic Physics

Electrons in atoms, when transitioning between energy levels, exhibit analogous behavior:

- Higher energy levels have larger orbital radii

- Lower energy levels have higher orbital frequencies

- Energy is released or absorbed during transitions

Rope and Pulley Systems

In rock climbing, sailing, and rescue operations, understanding how tension changes in ropes wrapped around cylinders or carabiners is crucial for:

- Safety calculations

- Equipment selection

- Predicting failure modes

Hurricanes and Cyclones

The spiral motion of air masses in cyclonic systems exhibits similar physics:

- Angular momentum conservation drives rotation speed

- Pressure gradients provide the inward force (analogous to tension)

- Wind speeds increase as air spirals toward the eye

Experimental Verification

Laboratory Setup

To verify this physics experimentally:

Equipment Needed:

- Air hockey table (frictionless surface)

- Lightweight puck (the particle)

- Thin fishing line (the string)

- Central post (the cylinder)

- High-speed camera

- Force sensor on the string

Procedure:

- Attach string between central post and puck

- Launch puck perpendicular to string

- Record motion with high-speed camera

- Measure tension continuously with force sensor

- Analyze trajectory, speed, and tension data

Expected Observations

Visual Observations:

- Clear spiral path with decreasing radius

- Particle speeds up its rotation (higher angular velocity)

- Path tightens more rapidly as it approaches center

Measured Data:

- Tension increases as radius decreases (following approximately 1/r³ relationship)

- Total speed decreases throughout the motion

- Angular momentum remains constant (within experimental error)

- Mechanical energy remains constant (confirming frictionless approximation)

Data Analysis

Plotting the data:

- Tension vs. Radius: Should show inverse cubic relationship

- Speed vs. Radius: Should show decreasing trend

- Angular Momentum vs. Time: Should be constant

- Energy vs. Time: Should be constant

Challenges and Sources of Error

- Air resistance (minimize with dense puck)

- String mass (use very light fishing line)

- Surface friction (use air hockey table)

- String elasticity (use inextensible material)

- Measurement precision (use high-speed camera and sensitive force sensor)

Related Physics Concepts

- Kepler’s Second Law: The conservation of angular momentum in our problem is the same principle behind Kepler’s second law of planetary motion: a planet sweeps out equal areas in equal times. As a planet approaches the sun (decreasing radius), it speeds up to maintain constant areal velocity.

- The Coriolis Effect: The spiral motion shares mathematical similarities with the Coriolis effect in rotating reference frames. Understanding one helps understand the other.

- Adiabatic Invariants: In advanced mechanics, angular momentum conservation in slowly changing systems is an example of an adiabatic invariant—a quantity that remains approximately constant when parameters change slowly.

- Central Force Motion: This problem is a specific case of central force motion, where a particle moves under the influence of a force directed toward a fixed point. Understanding the general theory illuminates specific cases.

- Virial Theorem: The relationship between kinetic and potential energy in bound systems (virial theorem) provides another perspective on why speed decreases while the system becomes more tightly bound.

The spiral motion of a particle attached to a string represents a beautiful synthesis of fundamental physics principles. The answer to the original question—option (c): tension will increase and speed will decrease emerges from careful application of conservation laws and force analysis.

Note:

- Conservation of angular momentum (mvr = constant) is the master equation governing the motion

- Tension increases due to the 1/r³ dependence of the centripetal force requirement

- Speed decreases because tension does negative work, removing kinetic energy from the system

- Tangential velocity increases while total speed decreases—a subtle but crucial distinction

- Multiple conservation laws must be applied simultaneously for complete understanding

The Bigger Picture

This problem exemplifies how physics often reveals counterintuitive results that become clear through systematic analysis. The increase in tension despite decreasing speed, and the decrease in speed despite increasing rotational velocity, remind us that physical intuition must be built on solid understanding of fundamental principles.

The mathematical framework we’ve developed—combining Newton’s laws, conservation principles, and energy analysis provides a template for attacking similar problems in mechanics. Whether analyzing planetary orbits, designing mechanical systems, or understanding natural phenomena, these principles remain our most powerful tools.

Final Thoughts

Understanding this problem deeply requires moving beyond memorization to genuine comprehension of how nature works. The interplay between different forces, velocities, and conservation laws creates a rich tapestry of physical behavior. By mastering this example, students gain insight not just into this specific scenario, but into the broader logic of classical mechanics that governs motion throughout the universe.

The elegance of the solution where seemingly independent observations about tension and speed both emerge from the same fundamental principles exemplifies the unity and power of physical law. This is physics at its finest: taking a complex, dynamic situation and revealing the simple, beautiful principles that govern it.

FAQs on Spiral Motion Systems

Q. Why does the speed decrease if there’s no friction on the plane?

This is one of the most common misconceptions about this problem. While it’s true that the horizontal plane is frictionless, this doesn’t mean no forces oppose the particle’s motion. The string tension itself does negative work on the particle as it spirals inward.

Think of it this way: as the particle moves closer to the cylinder, it’s moving against the inward pull of the tension force. Even though the tension pulls the particle toward the center, the particle’s total speed (not just the tangential component) decreases because the tension continuously removes kinetic energy from the system.

The absence of friction only means that energy isn’t dissipated as heat—it doesn’t mean the particle maintains constant speed. The tension force redistributes energy within the system, converting some of the particle’s kinetic energy into the work required to maintain the increasingly tight spiral motion.

Frictionless ≠ No forces acting on the particle. Tension does negative work, which reduces the total kinetic energy and thus the overall speed.

Q. If angular momentum is conserved (mvr = constant), shouldn’t the speed increase as radius decreases?

This question reveals a subtle but crucial distinction in physics. The conservation of angular momentum (L = mvr = constant) applies specifically to the tangential component of velocity, not the total speed.

Let’s break down the velocity into components:

- Tangential velocity (v_t): The component perpendicular to the string (going around the cylinder)

- Radial velocity (v_r): The component along the string (toward or away from the cylinder)

- Total speed (v): v = √(v_t² + v_r²)

The angular momentum conservation equation tells us that v_t × r = constant, which means the tangential velocity does increase as radius decreases. However, the particle also has a radial velocity component as it spirals inward, and the total speed depends on both components.

Due to energy conservation and the negative work done by tension, the total speed v actually decreases, even though the tangential component v_t increases. It’s similar to how a car might be accelerating in one direction while simultaneously braking overall—the net effect depends on all forces acting.

Note: Angular momentum conservation governs tangential velocity (v_t), but total speed (v) is governed by energy conservation, and these lead to opposite trends.

Q. How can tension increase if the particle is slowing down? Doesn’t higher speed require more tension?

This excellent question highlights why understanding the relationship between force, speed, and radius is essential. The tension required doesn’t depend simply on speed it depends on the centripetal acceleration, which is v²/r.

Here’s the crucial insight: even though the total speed decreases, the tangential velocity increases (from angular momentum conservation). The centripetal force requirement is:

T = m × v_t²/r

Since v_t = (constant)/r, we can substitute:

T = m × (constant)²/r³

This shows that tension is proportional to 1/r³. As the radius decreases, this cubic relationship means tension increases dramatically. If the radius is halved, the tension increases by a factor of 8!

Think of a figure skater spinning: as they pull their arms inward (decreasing radius), they spin faster (increasing tangential velocity) and must exert more force in their muscles to keep their arms moving in circles that’s the increased tension.

Point: Tension depends on tangential velocity and radius (T ∝ v_t²/r), not total speed. The 1/r³ relationship causes tension to skyrocket as radius decreases.

Q. What would happen if the string were elastic instead of ideal? Would the answer change?

Yes, the behavior would change significantly if the string were elastic (stretchable) rather than ideal (inextensible). With an elastic string:

Changes in the System:

- Energy Storage: Some of the particle’s kinetic energy would be stored as elastic potential energy in the stretched string

- Oscillations: The particle might oscillate in radius, bouncing between stretched and compressed states

- Complex Motion: The spiral path would likely include radial oscillations superimposed on the general inward motion

- Variable Tension: Tension would depend not just on the centripetal force requirement but also on how much the string is stretched

Impact on the Answer:

- Tension behavior would be more complex, potentially oscillating rather than monotonically increasing

- Speed changes would depend on the energy partition between kinetic and elastic potential energy

- The simple 1/r³ relationship for tension would no longer hold

However, the general trend would likely remain similar: tension would still tend to increase (on average) as radius decreases, and speed would still tend to decrease due to energy dissipation in the elastic deformation.

Note: The “ideal string” assumption is crucial for the simple, predictable behavior described in the problem. Real strings add complexity through energy storage and oscillations.

Q. In what real-world situations would I encounter this type of spiral motion?

Spiral motion with changing tension and speed appears in numerous real-world applications across physics, engineering, and nature:

1. Orbital Mechanics:

- Satellites experiencing atmospheric drag spiral inward toward Earth

- As they lose altitude (decreasing radius), their orbital speed actually increases

- This is why de-orbiting satellites speed up before burning up in the atmosphere

- The gravitational “tension” increases dramatically as they approach Earth

2. Figure Skating and Dance:

- When skaters pull their arms inward during a spin, they demonstrate angular momentum conservation

- They spin faster (increased tangential velocity) while the forces in their muscles increase

- Professional skaters can feel the increased tension/force required to maintain tight spins

3. Draining Water Vortices:

- Water spiraling down a drain exhibits similar physics

- As water moves toward the drain hole (decreasing radius), it speeds up its rotation

- The pressure gradients (analogous to tension) increase closer to the center

4. Particle Accelerators:

- Charged particles in synchrotrons follow spiral paths as they’re accelerated

- The magnetic fields (providing centripetal force) must be carefully controlled

- Understanding how force requirements change with radius is crucial for design

5. Hurricane and Cyclone Dynamics:

- Air masses spiral inward toward the eye of hurricanes

- Wind speeds generally increase as air approaches the center (though the eye itself is calm)

- The pressure gradients (driving forces) are strongest near the eye wall

6. Rope and Cable Systems:

- Rock climbing scenarios where climbers swing on dynamic ropes

- Marine applications with anchor chains and cables

- Understanding tension changes is crucial for safety calculations